The cost-effectiveness of referring patients for diagnostic imaging procedures, particularly early scans, is currently an important issue in the U.K., where the Department of Health plans to spend 2.4 billion pounds ($4.8 billion) to upgrade its diagnostic imaging services over the next five years. Naturally, the government is also enthusiastic about curbing unnecessary costs and optimizing the value of its investment.

The issue is particularly salient now, as general practitioners only recently received the right to refer directly to radiology for some exams under the Framework for Primary Care Access to Imaging program. Prior to the new guidelines, general practitioners were required to refer patients to a secondary specialist, such as an orthopedic surgeon, who could then order radiological studies. Advocates believe the new rules will lead to faster and more accurate diagnoses within the NHS.

ECR study

Researchers from the University of York addressed the cost-effectiveness of knee MRI in research presented at the 2008 European Congress of Radiology (ECR) in Vienna, Austria. The group conducted a multicenter randomized trial involving 553 patients with suspected internal derangement of the knee, including meniscal or ligamentous injuries. The researchers found the added charge for MRI referral to be a "cost-effective use of health service resources."

|

|

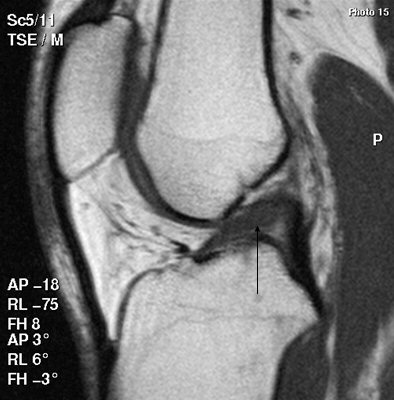

Above, scan shows a tear extending into the undersurface of the posterior horn of the medial meniscus. Below, patient has a torn anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), shown as discontinuity toward the upper end of the ligament, along with swelling of the lower part. All images courtesy of Dr. Stephen Brearley.

|

|

"The mean costs to the NHS of early access to MRI over 24 months is 1,315 pounds ($2,602), compared with 1,021 pounds ($2,020) for orthopedic referral," said Dr. Stephen Brearley, a research fellow at the university's Department of Health Sciences. "Early MRI is therefore associated with a higher NHS cost of 294 pounds ($582) per patient treated."

At 95% confidence intervals, the true cost of early MRI to the healthcare system should be considered to range from 31 pounds ($61) to 573 pounds ($1,135) per patient. "The number of GP or physiotherapist visits could also increase or decrease the cost of providing an MRI service," he added.

In an attempt to establish the overall value to the patient of performing early MRI, the research group employed the Short-Form 36-item health survey, a popular profile validated for use in the NHS to identify unexpected effects of interventions. Its physical functioning scale comprises 10 items designed to measure limitations when performing daily activities, such as walking and climbing stairs (a score of 100 is best health, 0 is worst).

Results indicated that while general practitioner referral to MRI increased patients' scores on this scale by 2.81 points, the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.072) compared with straight referral to an orthopedic specialist.

"The study was designed to detect a difference of 6.75 points on this scale. However, the 95% confidence intervals (from -0.26 to 5.89) exclude the difference of 6.75 points adjudged clinically important," Brearley said.

Improving quality of life?

Every study participant also completed an anonymized Knee Quality of Life (KQL) questionnaire. Eligible patients were between 18 and 55 years of age without chronic instability of the knee due to history of major injury, and who had not undergone a previous MRI scan or surgical intervention, or had suspected osteoarthritis or other nontraumatic arthropathy of the damaged knee.

Patients randomized to MRI showed a statistically significant (p = 0.014) improvement in their mean physical functioning scores by 3.28 points. The study found no other significant outcomes.

The final step in assessing the value of referring patients for early MRI was to present the cost-effectiveness results in terms of quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), an arithmetic product used by the U.K.'s cost-effectiveness watchdog, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). QALYs can be viewed as a "common currency" to assess the extent of benefits from various interventions in terms of health-related quality of life and survival for the patient.

NICE makes its recommendations on NHS' use of healthcare technologies, including diagnostic protocols and medicines, based on QALY data. A debate is ongoing in Britain as to the reliability of this expression of "value," however, QALYs are now used universally by authorities in making resource allocation decisions, such as whether an early MRI scan is a worthwhile addition to the diagnosis and health outcomes of patients with nonurgent knee injury.

"If you consider that a patient's health status (or QALY) ranges from 0 (death) to 1 (a year of perfect health), and therefore 2 QALYs reflect two years of perfect health, then the MRI group QALY over 24 months was 1.44 while the orthopedic group was 1.39. This is only a small health benefit, but it shows that patients in the MRI group had a larger number of QALYs by 0.05," Brearley explained.

"If you divide the mean difference in cost (between MRI scanning and standard orthopedic examination) of 294 pounds ($582) by the mean QALY difference of 0.05, this shows that access to MRI will cost 5,880 pounds ($11,653) per patient to generate an additional QALY (i.e., one year of perfect health)."

Therefore, he concluded, "GP access to MRI represents a cost-effective use of health resources" in the U.K., because although improvements in patients' knee-related quality of life are small, they are statistically significant.

Whether a general practitioner in the U.K. can now provide direct access for patients to MRI scanners may be limited still by the historic demands of fundholding general practitioners, who may not want to incur costs beyond their fixed budgets. In the 1990s, U.K. ministers created fundholding GP practices, in which GPs had their own budget to "buy" services, such as an MRI scan, directly for patients.

However, this was not universally applied across the U.K., and when the government eventually scrapped the system in 1997, some of these services (including several in radiology) remained available to the former fundholding GPs, while those who had not had access to their own budgets in the past were still denied direct access.

As a result of the legacy of fundholding, variation in MRI service provision across the country might reflect a more politically driven, rather than evidence-based, pattern. That said, it is estimated that nearly 1 million MRI exams are performed in England each year, and this level is expected to rise.

By Rob Skelding

AuntMinnie.com contributing writer

April 3, 2008

Related Reading

AAOS study: MRI overused for knee osteoarthritis, March 6, 2008

Study: Picking US over MRI for MSK imaging could save billions, March 6, 2008

Missed turn: What makes MRI detour in diagnosing meniscal tears? February 8, 2008

Studies uphold MRI's role in meniscal tears, propose new sequences, May 16, 2007

From tears to TKA: The ins and outs of knee MRI, September 5, 2006

Copyright © 2008 AuntMinnie.com